CHUNHUA ZEN ZHENG, Copyright 2001 Houston Chronicle Published 6:00 am CST, Tuesday, January 9, 2001

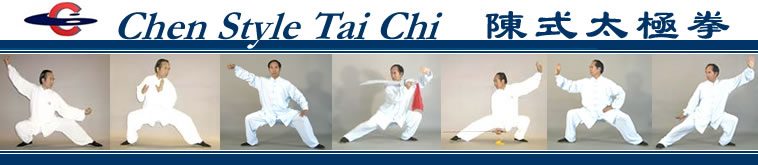

Stretching, bending, pushing and swirling in perfect unison and with deliberate slowness, scores of men and women, donned in white uniforms, moved as gracefully as wing-spreading swans hovering under the azure sky.

The afternoon sun highlighted their sways and turns and cast their shadows that swung like a smooth, melodic song.

Crowds of onlookers were enthralled by Jincai Cheng and his students’ execution of the art, called tai chi, at the International Chen Style Tai Chi Development Center in southwest Houston, during a recent public show. Sam Cheng, a student of Cheng’s, provided English narration for the spectators.

This picture of sunlight and shadows, and of paradoxes also seen in their movements — inhaling and exhaling, pushing and pulling, bending and stretching — was embodying a philosophy underlying the art being presented.

What the spectators saw was not just a mystical martial art form of self-defense and physical fitness. It was a demonstration of its fundamental concept of yin and yang — the contradicting yet mutually reliant forces believed to drive everything in the universe.

Spectators were intrigued as swords and long poles were used in demonstrations. They did not realize weapons could also be used in this elegant, dance-like art.

Misconstrued as only a fitness exercise, tai chi’s aggressive, combative side was shown as Cheng, 47, a man of medium build, was challenged by his award-winning student Robert Ernest Hubbard, who is 6-1, 290 pounds.

Cheng was as immovable as a rock as Hubbard lunged and yanked. Then with Cheng’s sudden twist, Hubbard found himself pulled uncontrollably and overturned to a collapse on the ground. He got up, tried again, to no avail. More attempts, third, and fourth . . . and one crash after another.

“The idea is to attack by yielding,” said Cheng. “You `borrow’ your opponent’s force and make use of his momentum.”

The finale came when Cheng headed a larger group in a meditative breathing routine. This time participants included old and young, neophytes and skilled practitioners alike.

Tai chi, an ancient Chinese martial art that teaches a mixture of internal energy cultivation and combative skills, is rooted in the Chinese indigenous religion of Taoism and Chinese traditional medicine. It is based on the theory that the universe is made of opposing but complementary forces, which can be balanced and reconciled to the benefit of life.

This ancient martial art has caught on in America, especially during the last decade. Tai chi classes and studios have mushroomed and attracted followers across the nation.

The scenario in Houston has an innovative twist. In addition to numerous indoor training programs, the Chinese tradition of practicing the art in groups in open public venues was brought to the southwest side of town where street signs are all in Chinese. At Diho square on Bellaire Boulevard, large groups of tai chi practitioners converge in the parking lot for their routines early each morning.

At Cheng’s studios, students respectfully call him “teacher,” a term traditionally used by the Chinese as an honor. However, unlike many teachers who operate tai chi programs in the nation, Cheng was recognized in 1992 as a grand master of Chen-style tai chi and is the only one in America who created a center dedicated to the style.

Cheng was born and raised in the village of Chen Jia Gou, the birthplace of Chen-style tai chi, in China’s northern province of Henan. As a prominent form of tai chi, Chen-style tai chi was said to be developed during the late 1600s by Chen Wangting, a military commander during the Ming Dynasty. The art passed down from one generation to another, only to male offsprings of the Chen family. Beginning the 14th generation, Chen-style tai chi also was taught to people outside the family who were highly respected in the community.

Cheng, suffering year-round dizziness and headaches as a child, decided to learn tai chi from his brother. Later, his fast progress prompted him to seek tutelage from Chen-style standard bearers, including 18th-generation grand master Chen Zhaokui and 19th-generation grand master Wang Xi’an. For his mastery, Cheng was listed as one of the only 10, 20th-generation grand masters in the lineage.

“My tai chi practice cured me of my headaches and dizziness in no time and for life,” recalled Cheng, whose complexion has a rosy glow.

He relocated to Houston for his import/export business in 1994, when tai chi was gaining ever-growing popularity in America, like the ancient Chinese divination practice Feng Shui. In Houston, however, Chen-style tai chi was little known and taught. Cheng, as the only recognized master of the style in north America, decided to spread the art.

He established his base at 9730 Town Park in southwest Houston in 1996, and later developed his second studio at 6732 Texas 6 S.

Al-asr Cordes, a martial art buff who has won numerous national and international awards, moved to Houston from Baltimore, Md., four years ago to devote himself to Chen-style tai chi. Under Cheng’s coaching, he reached mastery level and was appointed by Cheng to head Cheng’s second studio.

A third location in Sugar Land is being reorganized.

Students at Cheng’s center are of different nationalities. Currently numbered at about 160, their ages range from 6 to 73. Students come as far as Dallas and Louisiana to take lessons regularly.

“This is something everybody can do,” said Cheng. “You don’t have to be young or in shape to be a martial artist of tai chi. There are different types and levels to suit different capacities.”

At the show, a student with spinal deformity was as adept as others in his sword and long pole combat routines.

Tai chi is done with perfect fluidity, but occasionally punctuated with a sudden foot stamping or a fist pounding the hand — movements to release chi, understood as the energy channeling throughout the body.

According to Chinese traditional medicine, illness is the result of clogging of energy flow in the body. Tai chi, as Cheng’s students pointed out, healed their ailments.

Cordes said medical studies show tai chi enhances the immune system and has positive effects on a wide variety of ailments such as high blood pressure, asthma, Parkinson’s disease, arthritis, osteoporosis, digestive problems and even impotence.

“I had been plagued by my stomach problem for all my life, but tai chi cured it just in two months of my practice,” said Lucia Cheng, 62.

Tai chi restored Charlotte Jones‘s “borderline high” blood pressure to normal and knocked out Nancy Yue‘s sleeping disorder of six years, said the student.

In another evaluation, Brian Thompson said six months of his practice with Cheng stopped his life-long joint pain and improved his problem of short breath.

Though many students started the class in quests of physical fitness and healing, they were later enlightened on the art’s deeper, multifaceted benefits.

“Tai chi helps one realize the physical and mental potentialities and access an innate, transformative power that heals the body, calms the mind, and renews one’s strength,” said Laurie McDonald, a former ballerina.

McDonald decided to be Cheng’s student after she said she was inspired by Cheng’s “extraordinary grace and power” during a class observation.

“Tai chi is more than just a physical experience. Strength and skill are the outward expressions of the flow of chi. The practitioner’s strength comes from inside, from understanding chi and how the body acts as its distribution system,” she said.

“Whereas the ballet dancer achieves a type of physical look through muscle conditioning, the tai chi practitioner defies physical stereotyping because of this practice of internal conditioning. We come in all shapes, sizes, ages and physical conditions.”

Students agreed tai chi is a spirituality that, though with its lethal potential, helps one realize the oneness of oneself with the universe. It teaches the mind-set of harmony, as espoused in the ancient I-Ching, known as the Taoist fundamental Book of Change.

“With the techniques of tai chi, you can be invincible in a combat. But it’s not about fighting. It’s about internal self-development,” said Cheng.

“I give high rating to Master Cheng’s excellent school. It’s such a positive environment,” said Sheckeita Domeaux, a Ford Bend County resident whose 8-year-old son Frank Domeaux trains at Cheng’s studio on Texas 6.

“They do their job seriously. They teach frank physical skills as well as mental disciplines.”

Cheng, who has just released a demonstrative video, said he will continue the series so Chen-style tai chi can become everyone’s expertise. His future plans also include establishing branches throughout the country.

To know more about the art of tai chi and the programs Cheng runs, call 713-270-6797 or 281-568-8886, or visit www.chengjincai.com.