Original published on HOUSTON CHRONICLE newspaper section life Style & Entertainment on Jan.11, 1999

Written By MELISSA FLETCHER STOELTJE

Al-asr Cordes moves with the grace and fluidity of an underwater ballet.

Twisting and turning, swirling and lunging, his arms and legs sway in perfect time. It’s calming just to watch him.

This dance – this poetry – is more than meets the eye. It’s a philosophy, a mind-set, a way of viewing the universe. It expresses the very forces said to underlie all things: give and take, light and dark, soft and hard, yin and yang.

Cheng Jin Cai looks on. His student has learned well the ancient art of tai chi, a blend of self-defense, physical fitness and spirituality that has caught fire in 1990s America, of all places.

Across the nation, thousands have converged in classrooms and studios to practice the mystical martial art form, often described as meditation in motion. They follow in the steps of millions of Chinese, who for generations have made tai chi part of their daily routine. On any morning in China, in sprawling cities and tiny villages alike, one can find people, old and young, doing tai chi along dusty roads, in parks, in vacant lots.

The practice hasn’t reached that level in the United States, but tai chi teachers and classes have proliferated at martial arts studios and some health clubs; the Internet teems with tai chi sites. Tai chi, it seems, has become trendy.

But Cheng ‘s spacious, mirrored room in southwest Houston, where the street signs all speak Chinese, is not your garden-variety tai chi studio. And Cheng Jin Cai is not your garden-variety tai chi teacher.

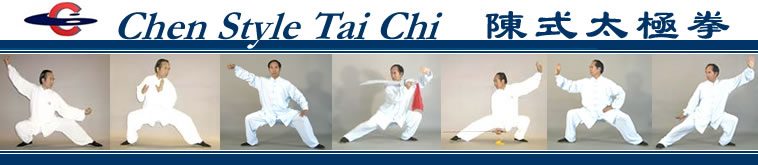

He is a grand master, born and raised in the village of Chenjiagou, China, the birthplace of Chen-style tai chi. Considered the origin of all other forms of tai chi, and its highest expression, Chen-style tai chi was developed in the 1600s by Chen Wangting, a great military commander and scholar who taught it to his warriors. For generations, Cheng -style tai chi was passed down from father to son, taught only to direct male descendants of the Chen family.

Cheng – or Teacher, as his students call him, using the Chinese honorific to denote respect – is not part of the Chen family. He learned tai chi from an elder brother as a child and went on to study under four of China’s foremost tai chi masters. Because of his skill, he was formally recognized in 1992 as a representative of the Chen family lineage, one of only 10 living Chen-style masters so named.

“Many say they teach Chen-style tai chi, but few can say they come from the village,” says Richard Huang, a longtime student who has come to the studio to interpret for Cheng, who speaks only basic English. “Master Cheng is the only (teacher) in the United States from the village.”

For someone who could cause serious harm with his bare hands, Cheng, 46, is a genial, unremarkable-looking man, with a calm smile and receding hairline. He has what looks like a regular build beneath his white tai chi uniform with a yin/yang symbol on the chest.

But watch as Cordes – who towers over Cheng and whose bulging thigh muscles can be detected even through his loose tai chi pants – tries to push Cheng over. He strains against Teacher’s abdomen with all his might, grimacing and grunting. Then, in a sudden movement, Cheng twists slightly, pulls Cordes’ arms and sends him flying to the floor with a painful crash. Cordes gets up, and Cheng does it again. And again, all the while smiling placidly.

You try. Cheng ‘s stomach feels elastic and soft – it has what the Chinese call peng, a word that describes the spongy feel of flesh infused with energy. Push with all your might. He’s immovable, like a wall. Then, before you know it, Cheng spins you off balance (delicately, this time).

With roots in Taoism, Buddhism and traditional Chinese medicine, tai chi is based around the premise of yin and yang – the idea that life is made up of two opposing but complementary forces, which, when balanced and reconciled, make up the whole. Active, passive. Male, female. Night, day. Tai chi is the embodiment of paradox.

And where other types of martial arts depend on “external” energy, explains Cheng , tai chi uses “internal energy.” Instead of brute strength, it’s based on subtlety, flexibility and being attuned to your opponent’s moves.

“A tai chi expert yields to his opponent, takes advantage of his momentum,” says Cordes, who runs a graphic design company with his wife (who also does tai chi). “You use his energy and add yours to it, causing opponents to defeat themselves.”

As a fitness method, tai chi – or the full name, tai chi chuan, which translates as “superior ultimate fist” – is the most egalitarian of exercises, says Cheng . Old and young alike can do it, even those who are out of shape or struggle with physical limitations. Students – currently, Cheng has 80 – start out learning basic steps and then gradually build to more elaborate routines.

“It’s based around individual ability; you don’t compete against others in class,” says Corky Dobbs, another longtime Cheng student. Dobbs, an investment company owner, came to tai chi after 26 years of international competition in weightlifting and bike racing.

Tai chi, he says, is not so much about strength as cultivating chi, or vital energy. This is achieved through slow, deep, conscious breathing, done in synchronization with movements that have lyrical, self-explanatory names like “Goose Spreads Its Wings” and “Buddha’s Warrior Attendant Pounds Mortar.” As Cordes does his routine, he inhales and exhales audibly with certain movements, breathing from his diaphragm. He is taut, yet loose; focused, yet relaxed. Occasionally, he pounds his hand in his fist, stamps a foot or slaps a leg. These are “explosive movements,” designed to release chi, which, according to philosophy, flows freely through the body.

The movements are designed to concentrate chi and push it down to the body’s center of gravity, located in the lower abdominal area.

“I do (tai chi) for a long period of time, and I feel chi in my back, sometimes tingling in my arm,” says Huang, a Taiwanese native and chemical engineer who now runs his own seafood company. “You ever feel that? It feels like little insects.”

“Yeah,” says Cordes, nodding his head.

During his routines, Cordes’ movements are excruciatingly slow and deliberate. But if you think tai chi is an easy workout, observe his forehead: It’s glistening with sweat.

“We can work out for 20 or 30 minutes, and our shirts will be dripping,” says Dobbs, who, like the other two students, has been studying with Cheng for more than three years. They take his class once a week, then practice their tai chi routines daily at home.

Cheng and Cordes give a demonstration of “push hands,” the tai chi version of competitive sparring. Cheng uses chin na, a series of swift, supple hand and arm twists that again immobilizes an opponent by yielding to him. The third and highest level of expertise translates as “cannon fist”; it employs Kung-Fu-like, rapid-fire movements that arise paradoxically out of the deliberate slowness of tai chi.

But true tai chi masters are rarely called upon to employ their potentially lethal expertise, having cultivated a worldview steeped in acceptance and oneness with the universe. This is not about fighting. Cordes, whose 2-year-old daughter often follows him in his routines, says tai chi, with its “holistic” emphasis, has made him more adaptable in the world.

But you get out of it what you put into it, he adds.

Most people approach tai chi simply for health reasons, says Dobbs, a Chinese-culture buff who practiced several different forms of martial arts before taking up tai chi.

“Not everybody understands the self-defense aspect of it, and the spiritual part . . . well, it takes years and years to get to that level,” he says.

Not that the health benefits are minor, they say. Tai chi offers a workout that is easy on the joints, compared with jogging or aerobics. Tai chi cured Huang of a chronic back problem, he says, and his wife of digestive troubles. Tai chi is said to boost the immune system, relieve stress, ward off osteoporosis. Some believe it is effective against some kinds of cancer and impotence. It’s been formally endorsed by the Arthritis Foundation as a way to relieve the pain of joint disease. According to traditional beliefs, says Cheng , human illness results when the natural pathways for chi get blocked or misdirected.

Tai chi may even increase life expectancy – one explanation, perhaps, for the legendary longevity of the Chinese. It’s nothing, says Cheng , to see 80- and 90-year-olds in China doing their morning tai chi routine.

Cheng himself was a sickly child, plagued by headaches and dizziness. Through tai chi, he says, he recovered.

He immigrated to the United States in 1994 for his import/export business. He continued to do tai chi as part of his personal regime, finding a place in front of a Chinese restaurant for his routine. Curious passers-by stopped to watch. A few requested lessons.

News of his expertise spread by word of mouth, and he began offering private lessons. He opened his studio, at 9730 Townpark Drive, in March. Many of his students have won medals at national and international competitions.

He is a true teacher, says Cordes.

“Some teachers teach only the pieces,” says Cordes, who credits tai chi for his not having been sick a day in the past 2 1/2 years. “Teacher teaches everything he knows. He doesn’t hold back information, like some others.”

Often, Dobbs says, his teaching method lies beyond words – a simple touch that corrects posture or explains a movement. And with an esoteric art form like tai chi, finding the right teacher is key.

“You can learn more from a good tai chi teacher in an hour than you can in a couple of years from a mediocre teacher.”